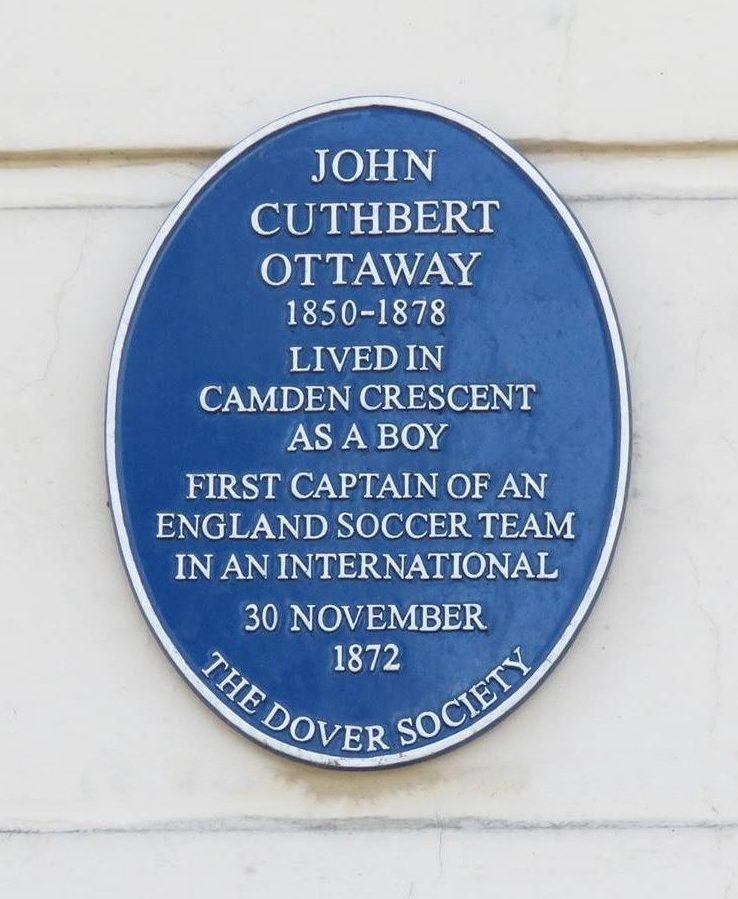

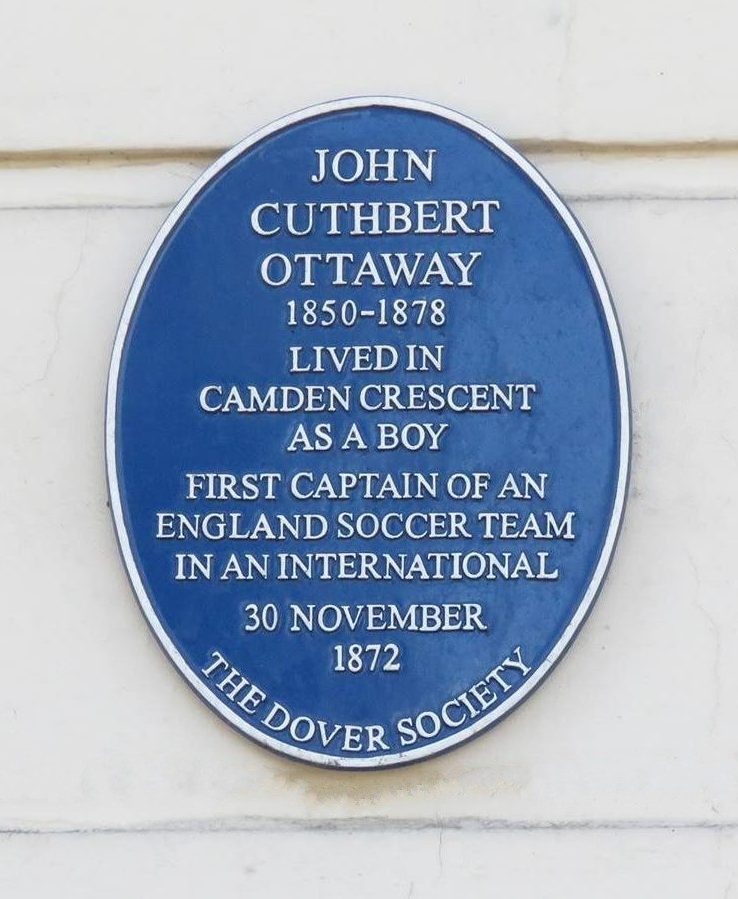

On Friday 16th March at Camden Crescent a plaque to commemorate a Dover man Cuthbert John Ottaway, was unveiled by Richard McCarthy a practising football referee, something of which Richard was proud. Richard was introduced to the gathering by Derek Leach who also expressed the Society’s gratitude to Ralph and Jean Bigrag who funded and gave permission for installation of the plaque and to John Hill, of John Hill Building Services, who installed the plaque without cost. Derek introduced Barry O’Brien who gave a history of John Cuthbert Ottaway, a presentation that left us all somewhat gobsmacked by Ottaway’s achievements accomplished in such a short life.

Cuthbert John Ottaway was born at 5 Hammond Place, Dover on the 19th July 1850. A “stone’s throw” from St. James’ Parish Church.

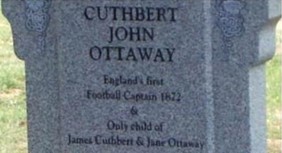

He died on the 2nd April 1878 and is buried in Paddington Old Cemetery.

He was the only child of James Cuthbert Ottaway a surgeon and former mayor of Dover in 1859. Educated at Eton, where he was a King’s Scholar, and at Brasenose College, Oxford,

England’s first football captain was arguably the greatest sportsman of his, or perhaps any era.

Cuthbert Ottaway lifted the FA Cup as skipper of Oxford University, represented them at five different sports ranging from athletics to real tennis, and once shared a 150-run partnership with WG Grace in the highest level of cricket.

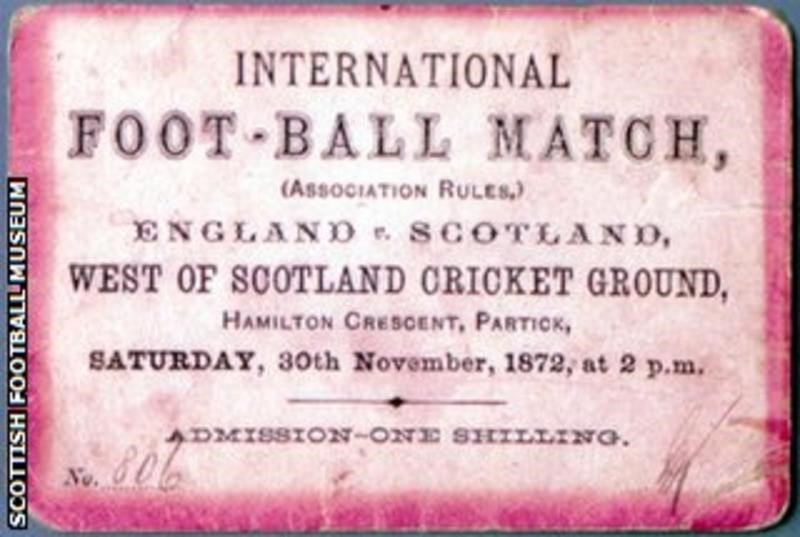

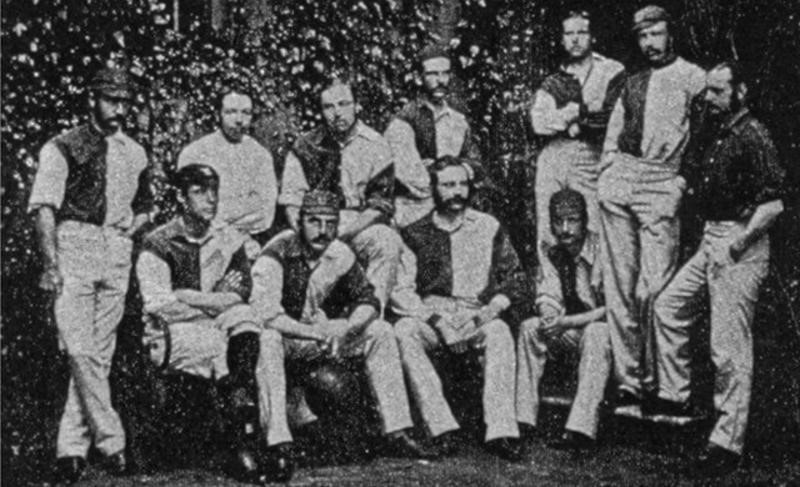

His most notable achievement was captaining England in the first ever international football match. About 4,000 spectators, including a “large number of ladies”, gathered to watch the historic game against Scotland at the West of Scotland Cricket Club in Partick on 30th November 1872. It was reported to have been an exciting match yet, like many an international friendly since, ended in a 0-0 draw.

So, Ottaway, who was also a barrister and died at the age of only twenty-eight after “catching a chill on a night out dancing,” had quite a sporting CV.

Yet when Michael Southwick, a handyman from Winlaton, near Newcastle, decided to find out more about this character with the olde-worlde name, he drew a blank. Even Ottaway’s place of burial was unknown. When Southwick finally traced it to Paddington Old Cemetery, he found a faceless stone slab, as the granite memorial it had once supported had been removed by Westminster Council in the 1970s. So, he set out on a three-year mission to write Ottaway’s biography, discovering a man of breath-taking sporting ability and versatility.

Ottaway first established himself as a sportsman at Eton, after winning a scholarship to the famous school. He won championships in rackets – a predecessor to squash – and played the Eton field game, their version of football.

But it was in the national sport of the day, cricket, that he truly excelled. As a 16-year-old, he played for Eton against Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), scoring fifty-five runs, and then went on to clock up nine centuries in a single season in 1869.

Later that year, he won a place at Brasenose College, Oxford, and went on to represent the University at the top level in five different sports – athletics, rackets, real tennis, cricket, and football – which remains a record.

Ottaway’s sporting genius reached its zenith in 1872. Following his 150-run partnership with Grace, the sporting superstar of the day, in a Gentlemen v Players match – the highest level of cricket at the time – he was invited to take part in a “Gentlemen of England” tour of North America. Effectively, it was an invitation to play for the national cricket team.

They played eight undefeated matches – five in Canada and three in the United States – with Ottaway opening the batting with Grace as well as keeping wicket. In the first match, against Montreal, he made nine stumpings and shared in a 100-run opening partnership.

During this time, football was emerging as a means for old-boys from different public schools to play ball games against each other.

And in November, Ottaway, fresh from his cricket tour of North America, was appointed as England’s captain for the first ever international football match, against Scotland. It is fair to say his side’s style of play was primitive.

“England would run with the ball in a rolling maul, like in rugby, but with the ball at the feet rather than in the hand,” says Southwick. A player dribbling would be protected by his team-mates barging opponents out of the way.

In contrast, their Scottish opponents ran forward in pairs, passing the ball between themselves. It was called the “combination game,” an early version of modern football. Anarchic and amateurish as the early game might seem now, Ottaway was undoubtedly an effective forward.

“He was a flair player,” says Southwick. “He was very fast – after all he was a sprinter and long jumper – and also agile. Pace would have been an important part of his game.” Exciting and historic the match may have been, yet it still ended goalless.

In March 1873, Ottaway played for Oxford University in only the second final of the Football Association Challenge Cup – the world’s oldest football competition, which became known as the FA Cup – against Wanderers at Lillie Bridge in London. His side lost 2-0 though.

A year later he made amends, captaining Oxford to a 2-0 win over the Royal Engineers at the Kennington Oval thanks to goals from Charles Mackarness and Frederick Patton.

Shortly afterwards, Ottaway captained Oxford University in their first varsity football match against Cambridge University, a match which must have been a bizarre spectacle.

All eleven Cambridge players stood on their own goal line for almost the entire game. Ottaway instructed his men to hang back and tempt the enemy out and eventually they scored to win 1-0.

In 1875, he played in his third consecutive FA Cup final, this time for Old Etonians against the Royal Engineers. The game, again held at the Kennington Oval, was played in a howling gale, and ended 1-1. It led to the convention of the teams’ swapping ends at half-time, to equalize the effect of the wind. Previously, teams had changed ends only when a goal was scored or if a half ended goalless.

This became Ottaway’s last-known football match, as in the 37th minute he received a “severe hack” to his ankle and was forced to leave the field and miss the replay, which the Royal Engineers won 2-0.

Ottaway subsequently married and began to focus on his burgeoning career as a barrister. Then, on 2nd April 1878, at the age of just twenty-eight, he died, from pneumonia caught on a night out dancing.

In the ensuing years, Ottaway seems to have been gradually forgotten. Until now that is.

Southwick’s biography of him was published in 2009 and read by Paul McKay, a player for the England Fans’ Football Club, who was “horrified” by the dilapidated state of Ottaway’s grave when he visited it.

He promptly set about raising funds for a new memorial and it was unveiled in a ceremony, while two commemorative football matches took place at one of Ottaway’s former clubs, Marlow FC.

Paul McKay and Mick Southwick standing next to the new memorial

The day before a friendly against Scotland at Wembley, England captain Steven Gerrard admitted he had only recently heard of Ottaway. “He had the honour of being the first England captain and it is great that what he achieved is being recognized in this way,” the Liverpool player said of the new memorial.

But for McKay, whose day job is as a senior manager at Nottinghamshire County Council, the battle to revive Ottaway’s name is not over. He is lobbying the FA to name a hospitality suite after him at St George’s Park, the national football centre.

“Bobby Moore’s grave would never have been allowed to go into that state of disrepair,” McKay says. “It is very difficult to compare the great Sir Bobby Moore with Cuthbert Ottaway, but he was England’s first football captain. Bobby Moore followed in his footsteps.”

Michael Southwick, wrote the book England’s First Football Captain

a Biography of Cuthbert Ottaway, 1850-1878.

When Fitz Fitzgerald’s cricket team from England toured North America in 1872, they played a match against Philadelphia over three days beginning on 21st September. The match was played at the Germantown Cricket Club Ground, Nicetown, Philadelphia. It was not a first-class fixture, the Philadelphians having twenty-two players and the visitors, who won by four wickets, having twelve. Amongst the English players were W. G. Grace, the future Lord Harris, and A. N. Hornby. Grace did little as a batsman but took twenty-one wickets out of a possible forty-two in the match.