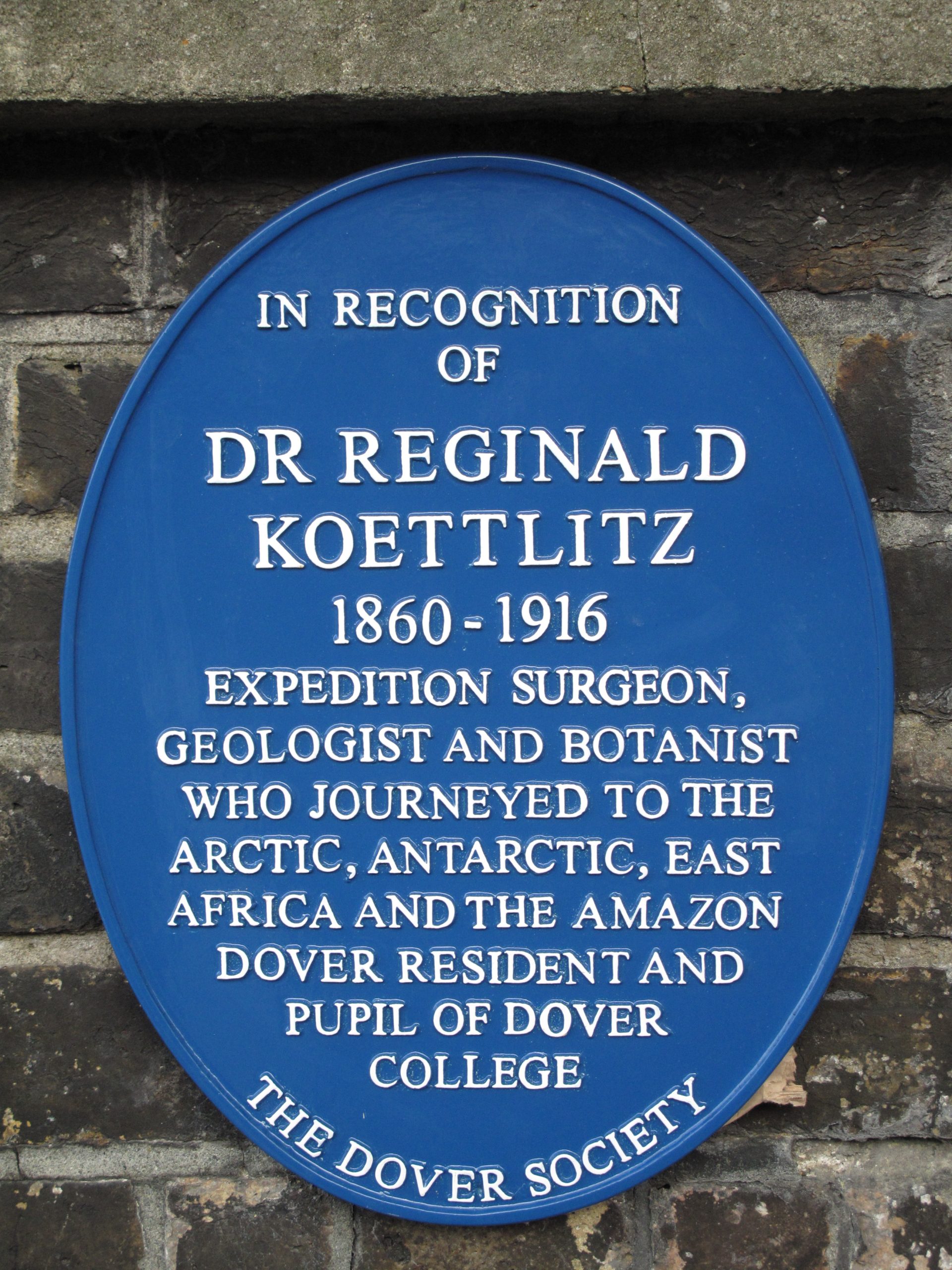

At 10am on Monday 5th December 2016 a ceremony took place to mark the installation of the latest Dover Society blue plaque. This was in recognition of Dr Reginald Koettlitz, a day boy at Dover College 1873-76, a Dover resident and arctic explorer. The plaque is installed at the old Gatehouse, Folkestone Road entrance to Dover College.

At 10am on Monday 5th December 2016 a ceremony took place to mark the installation of the latest Dover Society blue plaque. This was in recognition of Dr Reginald Koettlitz, a day boy at Dover College 1873-76, a Dover resident and arctic explorer. The plaque is installed at the old Gatehouse, Folkestone Road entrance to Dover College.

Our Chairman Derek Leach, the Headmaster of Dover College Gareth Doodes and Gus Jones all gave short speeches before the plaque was unveiled. A bouquet of roses was presented to Ann Jones nee Koettlitz.

The Dover Society would like to thank John Hall for his work on installing the plaque in its present position for which he did not accept any payment. We are truly grateful.

The following is taken from a talk to the Dover Society by Aubrey A. (Gus)

Jones and reported and updated by Alan Lee.

Scott’s Forgotten Surgeon

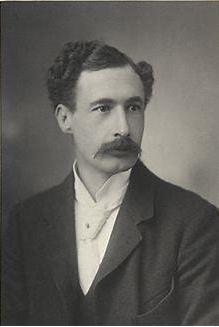

Dr Reginald Koettlitz – Polar Explorer

Dr Koettlitz came from an itinerant family which had moved from Konigsberg, in Prussia, to Germany, then Ostend, in Belgium, where Reginald was born on 23rd December 1860.

His father, Maurice, a minister of the Lutheran Church, with his family moved to Dover. By the late 1860’s they were living at 75/75 Folkestone Road, Dover where his mother, Rosetta, ran a boarding school. Along with Reginald were his three brothers Maurice, Robert and Arthur and two sisters Rosetta and Elise.

His father was a minister in the Reformed Lutheran Church, his mother, Rosetta Dowdeswell, an English teacher. They were a family of some considerable wealth but had fallen on hard times as a result of the gambling debts incurred by a previous minister of the church.

Shortly after Reginald’s birth the family were on the move again, this time across the Channel to Dover, where his father resumed his duties as a church minister.

In 1873 Reginald, along with his brother Maurice, entered Dover College He studied Greek, French and German which would prove to be of great help during his later expeditions. In 1878 he entered Guy’s Hospital to study medicine qualifying as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS). He then moved to Edinburg and graduated as Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians (LRCP Edinburgh). It was here he first became interested in geography and exploration.

He first post was as a general practitioner at Butterknowle, County Durham where he remained for nine years. Whilst here he was medical officer and public vaccinator for the Hamsterley district, Advisory GP to the Auckland Poor Law Union and surgeon to the Butterknowle, Woodland and New Copley collieries. In 1891 he was appointed Acting Surgeon to the 2nd Volunteer Battalion the Durham Light Infantry. Promoted to Senior Lieutenant in 1994 he then resigned his commission in June 1894, prior to joining the expedition to Franz Josef Land.

It was at Butterknowle that he became a member of the Barnard Castle Lodge of the Brotherhood of Freemasons.

In the early 1890’s he passed his practice over to his brother and cycled back to Dover from Durham. On 9th July 1894 he signed the papers and became a naturalized British subject.

Two days later he was aboard S.Y. Windward as she set sail from St Katherine’s Docks. He had secured a position as surgeon with the Jackson – Harmsworth expedition to Franz Josef Land at the North Pole. It was planned for a stay of between two and five years.

Owing to the pack ice it was decided to set up base at Cape Flora on Northbrook Island. They moved into their accommodation on 17th November 1894.

The base camp consisted of a single hut that provided only a basic and very cramped accommodation. In the first two years it housed eight men and in the third year seven men. Koettlitz had one of the three partitioned small individual areas (8ft x 5ft), the other team members slept on mattresses on the floor. Through periods of bad weather, owing to the cramped conditions in the hut, tempers were short, and many ridiculous arguments took place. For the first winter one party lived in the hut and the rest onboard the Windward which had become trapped in the ice.

They supplemented their dried and tinned rations with fresh meat which Koettlitz thought was essential to prevent scurvy. This included 94 polar bears, walrus, pony meat and loons (a species of bird). The men ashore all ate fresh meat regularly and were not affected by scurvy many men on the ship refused fresh meat and were.

The polar bear he brought back from this expedition stood in his brothers’ surgery at Charlton House, London Road for many years. Now on display at Dover Museum it is still in an excellent condition and an impressive sight.

Koettlitz proved to be adept working with his hands. Over the winter he made himself garments from animal skins, a pair of boots and a face and nose mask. He made snowshoes for the ponies and harnesses for the ponies and dogs. During his stay he continued to develop and improve the tents and added a secure entrance. Until a few years ago this was still the preferred style in use.

Much of the uncharted part of Franz Josef Land was mapped and some islands and features named after expedition members. One such was Reginald Koettlitz Island. After three hard years they agreed to return and left aboard the Windward on 6th August 1897 and arrived at Erith on the River Thames in September.

On his return to Dover, he produced a substantial paper for the Royal Geographical Society in London detailing the construction, size and shape of the islands visited illustrated with many detailed drawings and diagrams.

He gave a series of lectures, one in the Norman Hall of Dover College, to the pupils and townspeople. This was reported in the Dover Telegraph at the time.

Between lectures he joined the Blundell Expedition to Northeast Africa and completed a solo trip up the river Amazon.

By 1899 the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Society were planning a joint venture to the Antarctic. By now a well-known and successful, but slightly eccentric, expedition surgeon, geologist and botanist Dr Koettlitz wanted to be part of it.

After much disagreement Lieutenant (later Commander} Robert Falcon Scott, an experienced naval officer but with no polar experience, was appointed leader. Koettlitz was invited onto the small select committee to plan what provisions and equipment to take. Then in March 1900 his inclusion in the expedition was confirmed.

Never a rich man and to raise funds he was appointed as the ships doctor aboard the Red Cross Line steamer Sobralense on its voyage up the Amazon to Manaos.

During his short time away the building of their ship the Discovery continued and by May her sea trials had been completed.

For some time, he had been courting a 38-year-old Calais woman Marie Louise Butez and decided that they should wed before he left for the Antarctic. They were both living in London and married on 2nd March 1901 at Chelsea Registry Office. Ernest Henry Shackleton, later destined to become one of the most famous polar explorers, attended the wedding.

The expedition set of on 5th August 1901 from the East India Dock, London. During the voyage Koettlitz’s appointment as ‘Chief of Scientific Staff’ was confirmed. Scott disregarded this and despite his lack of suitable qualifications and experience conferred that title on himself.

Only Armitage and Koettlitz had direct experience of polar survival for any length of time while Bernacchi had a little. Overall, this meant that the expedition was very inexperienced.

Some interesting, and unusual, items were listed as ‘Medical Comforts’; 27 gallons of brandy and whisky, 60 gallons of port wine, 36 gallons of sherry and 36 gallons of champagne. To enhance morale on the lower deck 1,800lbs of tobacco was also stowed away.

After a stopover in New Zealand by February 1902 the Discovery was at the head of McMurdo Sound and had found a safe place to overwinter. By the 14th building of the base camp was progressing well and the stores had been landed.

Dr Koettlitz

Koettlitz and Armitage had serious concerns over the lack of any training with skis, dog handling, pitching tents and preparing food in freezing conditions. To their dismay recreational pursuits took preference over survival training. This concern was confirmed when half of the first sledging party, all wearing unsuitable equipment and the wrong type of boots, returned and seaman Vince fell over an ice cliff and was killed.

Scott led the next party, to set up a provisions camp, but left his experienced men behind. He took no skis and only a few out of condition dogs, intending mainly to manhandle the sledges. This was the ‘British Way’ but was against all experienced wisdom. After three days of arduous effort Scott had only managed ten miles. They left their stores there, gave up the journey, and returned to the ship.

During the first winter the temperature dropped to -94°F (-62°). As per naval tradition every Sunday the decks were scrubbed, and the men had a formal inspection. This risked frostbite, but still no sledge training. It was not until August that an attempt to form the dogs into efficient teams was tried. He was not impressed with the ‘make do and mend’ attitude of the expedition. It was not until August that any attempt at getting the dogs formed into efficient teams was tried.

By the spring, after returning from a trip, he encountered a serious problem, scurvy. Nearly everyone had it they had not been eating fresh meat. Up to now Scott had had refused to sanction killing wildlife to obtain fresh meat. After reversing this decision, the scurvy soon cleared up.

Scott when told not to pull the small boats up on to the ice ignored this advice and they became covered in ice and snow. This necessitated a lot of extra hard work to cut them free.

During the ‘sledging season 1902-03 he discovered a huge glacier, later named ‘Koettlitz Glacier’, even today it is still a huge size.

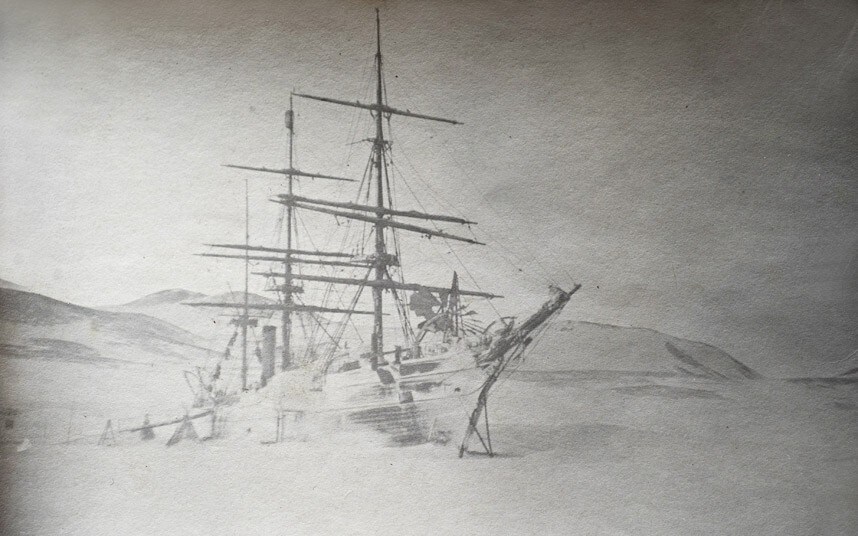

Koettlitz Glacier The Discovery

In 1903 Scott forced Shackleton to leave. Later Armitage was to write that Scott stated, “if he does not go back sick, he will go in disgrace”. Scott had not forgotten Shackleton’s challenge to his authority on the voyage out. He also tried to remove Koettlitz and Armitage, but their contacts precluded it.

The first coloured photographs of the continent were taken by Dr Koettlitz between February 1902 and November 1903. He took 53 colour images but all photographs, plates and his expedition journal went missing and have never been found. It is also recorded that Scott instructed that no prints were to be made from any of the plates.

After being icebound for so long on the 14th of February 1904 the rescue ships reached the discovery. They sailed for New Zealand and a tremendous reception.

On his return to England Scott excluded virtually all of his work from the final expedition reports and Koettlitz was unhappy about the amount of serious work he had been allowed to undertake.

On returning to Dover in 1904, Koettlitz gave one extended lecture in Dover Town Hall where he displayed the first colour images taken on the Antarctic continent. He was an accomplished photographer but, as with much with regard to Koettlitz, these images were handed to the expedition managing committee and have been lost to science and the nation.

Despite this lack of official recognition his collections from Antarctica list some 540 items with a further 288 marine items and many medical records all in great detail. None of his work is mentioned in the final scientific report of the expedition.

Returning to Portsmouth selected members of the crew, including Koettlitz, were awarded the new polar medal. He received his by post when in South Africa in 1905. They then sailed up the Thames and the Discovery berthed in the East India Docks, Port of London.

Scott, now a captain, was invited to Balmoral by the King. He took Dr Wilson’s excellent sketches and Skelton’s black and white photographs but ignored the colour ones taken by Koettlitz.

Back in Dover he had not been forgotten. On Wednesday 11th January 1905 a civic reception was held for him at Dover Town Hall. Here he gave an illustrated lecture entitled “Furthest South” which lasted two hours. The new three coloured process, perfected by him, was used for the first and only time in public.

Shackleton invited him to join his Nimrod Expedition to the Antarctic, this turned back 97 miles from the South Pole, he declined but helped with the preparations.

As something of an outsider on the expedition, therefore, Koettlitz was pushed into the shadows on its return. Although he had been made chief of scientific staff, his position wasn’t recognised in Scott’s book of the expedition, The Voyage of the Discovery. Worse, none of his work featured in the expedition’s final scientific reports. Even a report to the British Medical Journal was presented by Koettlitz’s deputy on the ship. This falling out with the polar establishment led ultimately to his move to South Africa, where he practised as the resident doctor in the expanse of the Great Karoo.

When his wife Marie lost their only child at birth they agreed to move to South Africa. He obtained a general practice on 22nd June 1905 in the Somerset East District, now the Eastern Cape Region. He was based at Grobbelaars Kraal, Darlington which now lies at the bottom of an artificially enlarged Lake Mentz. A member of the masons he transferred to the local lodge. He was appointed a Justice of the Peace.

In June 1915 they moved to Somerset East. Shortly afterwards, on 5th January, both being in poor health, they were taken to Queen’s Central Hospital, Craddock.

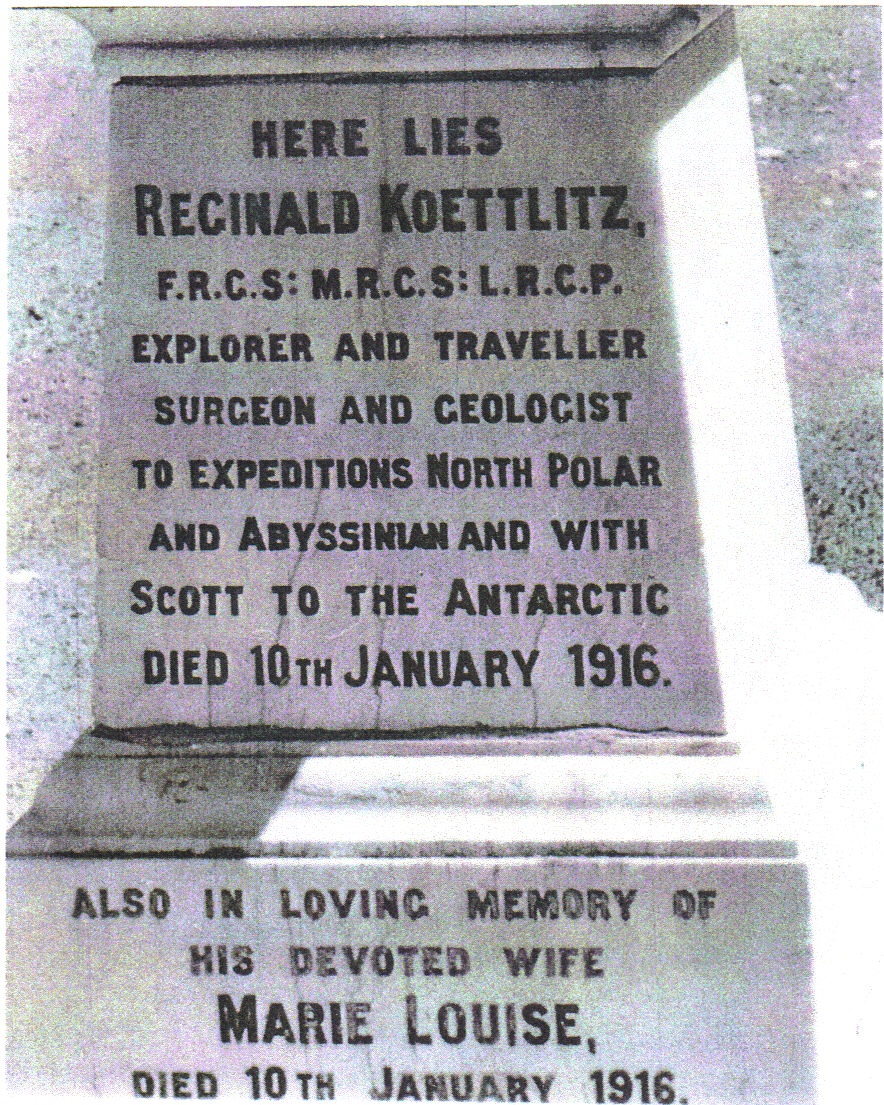

On January 10th 1916, in the small Karoo town of Cradock, South Africa, Dr Reginald Koettlitz passed away within two hours of his wife, Marie Louise Butez. He died of dysentery, she of heart disease. When news reached Somerset all flags in the town were flown at half-mast.

They were buried in Craddock cemetery. Obituaries appeared in the Lancet, national and local newspapers in New York, Australia, Britain and New Zealand.

Cradock Cemetery South Africa Grave Marker Vortrekker Street Cradock Eastern Cape South Africa

Apart from in Dover he is largely forgotten in England. In 1922 the Rev C W Wallace, Rural Dean of Craddock campaigned for a memorial. This is now positioned over his grave. There is no memorial in England, just a polar bear shot by him on Franz Jozef Island now on display in Dover Museum.

To really find his fitting honours, though, you have to go to the ends of the earth: To the Koettlitz Glacier, one of Antarctica’s largest, and to Reginald Koettlitz Island, part of Franz Josef Land, both named in his honour.

References to Dr Koettlitz can be found in the Dover Society Newsletters No. 50 page 21, No. 55 page 16, No. 79 page 25 and No. 88 page 33. On Dover Museum website under the collection Polar Bear. An article The Polar Explorer Frozen Out of History by Gus Jones can be viewed by typing in www.theneweuropean.co.uk-koettlitz. The book Scott’s Forgotten Surgeon by Aubrey A. Jones can be obtained from bookshops or online from www.booksfromscotland.com.